The Fallacy extravaganza of online debating

- William

- Aug 15, 2019

- 4 min read

Whenever I watch a Ray Comfort Living Waters video or talk to christians who follow him, or Frank Turek, I can grab some bingocards and start playing some fallacy bingo. Especially when Ray Comfort talks to one of those 'pesky' atheists. For those of you who don't know Ray Comfort, A: you should feel lucky and 2: he is a streetpreacher who talks to people about Christianity, for which he uses a couple of 'go to' arguments.

When talking to Atheists, Ray has one specific 'go to' argument. When he asks the Atheist 'Do you believe in God' and the answer is 'No', his immediate reaction is "so you believe the scientific impossibility that nothing exploded in to something and created everything"

This ofcourse is a logical fallacy. The conclusion Ray draws, does not follow from what the Atheist said. The logical fallacy Ray commits here, is the product of his aversion against Atheism. He projects his own biased interpretation of what an Atheist might believe about the origin of the universe, on to the person he talks to.

Ray knows this is wrong, he has been corrected on this, many times, but he doesn't change his narrative. By ridiculing Atheism he distances himself from what the Atheist really believes. This seems to be a self-defense mechanism. By ridiculing an opposing view, it is easier to hold on to your own beliefs. And it seems Ray is willing to use logical fallacies to do so. And the non-sequitur is one he falls back on often.

Fallacy extravaganza

A Non-Sequitur describes a fallacy where the conclusion does not follow from the argument or arguments. I found this to happen a lot when discussing with theists online. People use loaded questions, pre-suppositions, non-sequiturs and a whole bunch of other fallacies. It can be a real fallacy extravaganza at times.

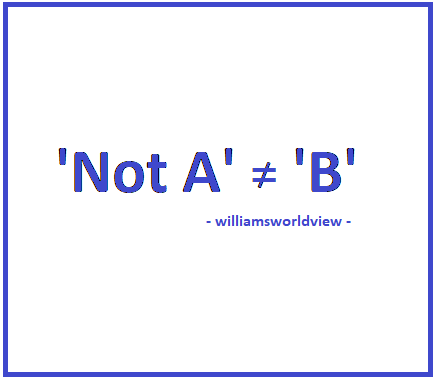

Recently I had a long discussion with someone about, how my answer to his 'false dichotomy' was not a real answer. He stated that everything was either A 'created by an intelligent mind' or B through 'random processes'. My answer to his somewhat flawed statement, was "Not A" which he immediately presumed to be "B". This however is not the case. Option 'B' is far to vague to judge, so I didn't. Option A didn't have that problem so I could easily discard that. Making "Not A" a valid answer. He disagreed.

The principle "Not A does not equal B" was foreign to him, apparently, and even when I used an kindergartenlevel example to explain it to him, he still objected, claiming that my logic was flawed. Somehow I often find myself resorting to kindergartenlevel explaining, when I am in such a discussion. The example I used was:

If you go to a fastfood restaurant and you get asked "Which condiment do you want with your fries? A: Mayonaise or B: Mustard" then the answer "Not A" doesn't equal "B". There are many more condiments you could put on your fries and of course you could also opt not to put any condiments on your fries.

Mayonaise (in some parts of the world) is a rather common condiment to put on your fries. Mustard however is not. So, you could easily decide not to want Mayonaise. Since Mustard is a less common condiment to put on fries (tried it, was actually quite nice) you could take a bit longer to decide if you want it, or if would like to ask if there are other condiments available. Whilst deciding on option "B", the intermediate answer "not A" is a valid response. Basically it is the short answer for "Not option A, but I haven't decided on option B, yet".

Just because a premiss doesn't specify all the options, that doesn't mean those options are not available. And this is the thing, I suppose. Identifying fallacies before responding to them is important. And I do call those out, by explaining how I feel the question asked, or the premiss stated, is based on a wrong premiss of false information. You can correct that, and then have the question reasked properly.

However there is one situation you want to look out for. And this is something I have seen well known apologist Frank Turek do several times in his lectures, speeches and debates. When a certain type of question is asked that doesn't fit his narrative then he rephrases it slightely, changing the nature of the question.

By answering his own question he can stick to his narrative and still seem to have answered the persons question. This is just as fallacious as asking a loaded question or stating a false dichotomy. And actually it is a trick politicians use often during their debates, as winning points there can have some political results.

I just picked a couple of examples. But when you do discuss online, you will see this happening a lot. From unintended Red Herrings to blatant Adhominem attacks. The range of fallacies seems to be infinite. Which can make it either funny or frustrating.

Me recognizing some fallacies ofcourse also means I use some fallacies myself. They can be usefull at times. So, I do use them to make a point, win a point or when I am in the right mood, I use them for some personal entertainment. But that's just me being a dick at times.

I do tend to be a dick at times, wich usually happens when the discussion stalls, because the people discussing eachother don't understand eachother, people don't see the fallacies they commit themselves, or when there is some blatant intellectual dishonesty.

Anyway, all that still hasn't made me stop entertaining myself with some online debates. When you enjoy these kind of online discussions and debates, I'm sure you share these experiences and perhaps even have enjoyed a nice little Fallacy Festival every once in a while.

コメント